Monday, December 29, 2008

Tuesday, December 23, 2008

An India Edit. - I want to narrow these down- HELP

From the moment I began telling stories, listeners pleaded to hear my memories of India. I had been three times by the age of thirteen, but I was ashamed that the absence of a genuine memory overwhelmed me when I attempted to describe my experiences there.

Despite my being a conscious person while wandering through the streets, it was as if a hazy, sleep-deprived version of myself had actually lived it. I could only recall the confusion I felt while being there. I wondered how a place so different from my home could be my father’s home. As soon as I landed back in the comfort of familiarity in the United States, part of me began discarding the discomfort of the culture that I visited.

Instead of sharing how unsure I was about what had really happened to me abroad, I just tried to talk – say anything that drifted slowly and carefully through my mind and landed gently on my tongue. My words described the curious vendors on the street, the strange fruits I ate for breakfast. I was afraid to say the wrong thing or reveal too much of my flimsy knowledge. There were so many things I wanted to say, but I did not know how.

I distinctly remembered the burning on my lips from the chilies and the intense heat on my skin from the sun’s rays. I remembered how the hot kisses on my forehead from my family awaiting our arrival made me feel warm from my spine to fingertips. I remembered the warmth of most everything with poignancy. It was as if the heat of the entire city of Mumbai was the first thing to ever make me sweat.

When I tried to recount this, I would inevitably just feel cold. I wanted my observations to be unique, authentic. In order to piece together a real history of what India means to me, I went flew back alone and began asking the questions that had been swirling around and consuming me in every previous trip. After spending hours and days in the Pinto Hospital, I can begin to truly share an element of India that relates to me. This is the story that I have always wanted to tell. It is a tradition that my grandparents began and my aunt continues today. It is a place that both fascinates and defines me.

My Grandparents. The images of the late Drs. Denise and Charles Pinto hang in the entrance way to the hospital. They opened the hospital in 1947, two years before my father was born.

The Waiting Room. Finding it too difficult to make appointments for the many patients she sees, Dr. Sunita Pinto created daily office hours for people to have check-ups. Most women come alone to see the doctor, but some have interested husbands or concerned mothers who tag along.

Dr. Pinto has a direct line from her apartment on the fifth floor to the hospital three stories below. She makes herself constantly available to her staff by telephone and when traveling to parts of her neighborhood that don't have service, she calls to let them know where she will be. If need be, someone would physically come reach her in case of a medical emergency.

C-Section. Although Dr. Pinto does most deliveries alone, when a more complicated procedure is necessary she requires the help of a team of other doctors. This c-section was especially difficult because the mother had a history of cysts on her uterus. The doctors were careful to not cause a tear to the scarred walls during the operation.

Every month, a few perfectly healthy women will wait during office hours to pop in with their toddlers to thank Dr. Pinto for her care during their pregnancy. When she walks down the streets of her neighborhood, it is inevitable that she runs in to a former patient with grown children who greet her with a smile. Many of the children in the area have the pet names “Pinto and Pinti” for their having been born in the Pinto Hospital.

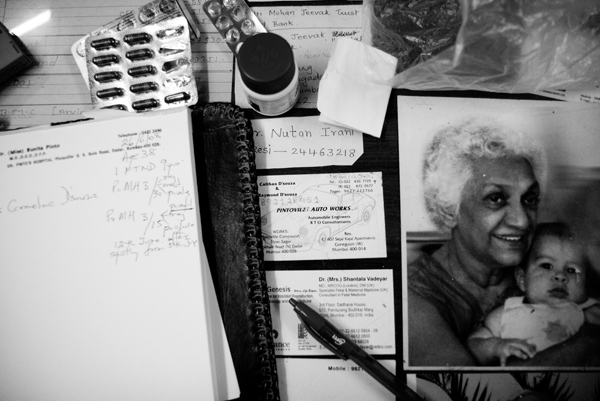

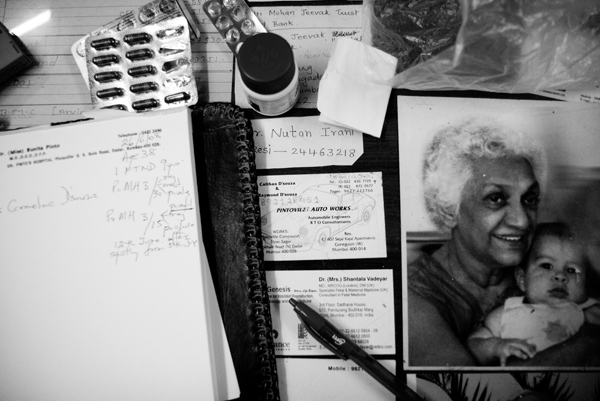

In place of having file cabinets filled with patient records, Dr. Pinto writes up a summary of each patient's pregnancy on a note pad and insists that the women bring the paper back - clean and unwrinkled - to their next appointment. Her desk is decorated with an image of her mother and one of her many grandchildren and a scattering of various free medicine samples.

Ayahs have the responsibility of cleaning the hospital, cooking meals for the mothers, and tending to newborn babies. Although primary education up to college is free for all Indian women, many of the ayahs are uneducated and have only been taught to cook and clean through their upbringing.

The small hospital requires the attention of all staff to function efficiently. Here, an ayah and three nurses await direction from the doctors performing a hysterectomy.

Women are eager to be reassured that their pregnancy is progressing well and to hear a normal heartbeat of their unborn child. Although Dr. Pinto answers any questions the patients may have, it is illegal in India to release the sex of the child to the parents before birth in order to prevent abortions on female fetuses.

Once cleaned, weighed and clothed, newborn babies drift to sleep as their mothers are cared for post-operation.

Despite my being a conscious person while wandering through the streets, it was as if a hazy, sleep-deprived version of myself had actually lived it. I could only recall the confusion I felt while being there. I wondered how a place so different from my home could be my father’s home. As soon as I landed back in the comfort of familiarity in the United States, part of me began discarding the discomfort of the culture that I visited.

Instead of sharing how unsure I was about what had really happened to me abroad, I just tried to talk – say anything that drifted slowly and carefully through my mind and landed gently on my tongue. My words described the curious vendors on the street, the strange fruits I ate for breakfast. I was afraid to say the wrong thing or reveal too much of my flimsy knowledge. There were so many things I wanted to say, but I did not know how.

I distinctly remembered the burning on my lips from the chilies and the intense heat on my skin from the sun’s rays. I remembered how the hot kisses on my forehead from my family awaiting our arrival made me feel warm from my spine to fingertips. I remembered the warmth of most everything with poignancy. It was as if the heat of the entire city of Mumbai was the first thing to ever make me sweat.

When I tried to recount this, I would inevitably just feel cold. I wanted my observations to be unique, authentic. In order to piece together a real history of what India means to me, I went flew back alone and began asking the questions that had been swirling around and consuming me in every previous trip. After spending hours and days in the Pinto Hospital, I can begin to truly share an element of India that relates to me. This is the story that I have always wanted to tell. It is a tradition that my grandparents began and my aunt continues today. It is a place that both fascinates and defines me.

My Grandparents. The images of the late Drs. Denise and Charles Pinto hang in the entrance way to the hospital. They opened the hospital in 1947, two years before my father was born.

The Waiting Room. Finding it too difficult to make appointments for the many patients she sees, Dr. Sunita Pinto created daily office hours for people to have check-ups. Most women come alone to see the doctor, but some have interested husbands or concerned mothers who tag along.

Dr. Pinto has a direct line from her apartment on the fifth floor to the hospital three stories below. She makes herself constantly available to her staff by telephone and when traveling to parts of her neighborhood that don't have service, she calls to let them know where she will be. If need be, someone would physically come reach her in case of a medical emergency.

C-Section. Although Dr. Pinto does most deliveries alone, when a more complicated procedure is necessary she requires the help of a team of other doctors. This c-section was especially difficult because the mother had a history of cysts on her uterus. The doctors were careful to not cause a tear to the scarred walls during the operation.

Every month, a few perfectly healthy women will wait during office hours to pop in with their toddlers to thank Dr. Pinto for her care during their pregnancy. When she walks down the streets of her neighborhood, it is inevitable that she runs in to a former patient with grown children who greet her with a smile. Many of the children in the area have the pet names “Pinto and Pinti” for their having been born in the Pinto Hospital.

In place of having file cabinets filled with patient records, Dr. Pinto writes up a summary of each patient's pregnancy on a note pad and insists that the women bring the paper back - clean and unwrinkled - to their next appointment. Her desk is decorated with an image of her mother and one of her many grandchildren and a scattering of various free medicine samples.

Ayahs have the responsibility of cleaning the hospital, cooking meals for the mothers, and tending to newborn babies. Although primary education up to college is free for all Indian women, many of the ayahs are uneducated and have only been taught to cook and clean through their upbringing.

The small hospital requires the attention of all staff to function efficiently. Here, an ayah and three nurses await direction from the doctors performing a hysterectomy.

Women are eager to be reassured that their pregnancy is progressing well and to hear a normal heartbeat of their unborn child. Although Dr. Pinto answers any questions the patients may have, it is illegal in India to release the sex of the child to the parents before birth in order to prevent abortions on female fetuses.

Once cleaned, weighed and clothed, newborn babies drift to sleep as their mothers are cared for post-operation.

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Anachronism: Right Place, Wrong Time

There is now a full-screen option in soundslides. Click that bottom right icon to get a better look at our images.

Tuesday, December 09, 2008

More practice in portraiture

Thursday, December 04, 2008

Multiple Flash

Tuesday, December 02, 2008

Multimedia Scoping

Although I am still stuck in the phase of creating audio slideshows, I am well aware that photojournalists are going to be required to produce great video in order to compete in many markets. For Advanced Techniques, we were asked to share some recent multimedia we enjoy. Two things stuck out in my mind: one from Mediastorm, the other from New York Times.

http://mediastorm.org/0024.htm

This piece is so well done, but beyond devastating. Watch only if you are prepared for a mesmerizing sadness.

http://www.nytimes.com/packages/html/politics/2008-election-overview/?ref=multimedia

This piece was unveiled on election day and surprised me with it's uniqueness and depth. It has since been edited to include Obama's win which makes me even happier. It includes photos, audio, video, maps and a lot of fancy Flash work. I could watch it over and over.

http://mediastorm.org/0024.htm

This piece is so well done, but beyond devastating. Watch only if you are prepared for a mesmerizing sadness.

http://www.nytimes.com/packages/html/politics/2008-election-overview/?ref=multimedia

This piece was unveiled on election day and surprised me with it's uniqueness and depth. It has since been edited to include Obama's win which makes me even happier. It includes photos, audio, video, maps and a lot of fancy Flash work. I could watch it over and over.

Monday, December 01, 2008

I'm an American - Indian, not an Indian - American. Or something...

I traveled to India in the summer of 2008 for a plethora of reasons. Primarily, I was sideswiped by a dump truck and the first two things I did with the pain and suffering check were to buy an entire camera setup and a round trip ticket to Mumbai. I had returned to my father’s native country a handful of times growing up, but it always felt that when I landed back in the States, I only picked up a few hilarious dirty words in Hindi and a dense confusion as to how a country I didn’t understand could be half of who I am.

This time was going to be different, in my mind. At 19, I felt like I was enough of an adult to approach this trip with both career and personal goals. I traveled to the country for five weeks in hopes of making it less like a vacation and more like a cultural immersion. I dreamt that when I left I would have a grasp on the context of India, enough that I could someday work there as a photojournalist. At the end of the five weeks, I had an innumerable amount of glorified travel images instead of a strong body of work. My personal goal –understanding what part of me was truly and Indian- didn’t go as planned either.

Landing in the hectic and unstoppable motion of Mumbai has always made me feel self-conscious and realistically - very very white. The curious stares from seemingly everyone on the streets created a hyperaware attention to the language I chose, the clothes I wore, and the big expensive camera hanging around my shoulder. This trip in particular – traveling alone and with a purpose – caused an identity crisis I wasn’t prepared to deal with.

The most emotionally difficult experience I had in India was as a tourist with my Aunt Sabrina, my cousin Suhail and his wife Mrunalini. We spent a week in the North, a region of India I had never before seen. The beauty of the place astounded me. It forced me to abandon the images of crowded streets and polluted walkways that I associated with India and begin to absorb the diversity and complexity of the country I was visiting. Snow-capped peaks of hills in the Shiwalik Range of the Himilayas surrounded me and we wandered through small towns that managed to eloquently blend the traditional customs of the people with the undeniable comfort of restaurants and shops that could have accepted credit cards.

My genuine joy and gratitude for the experience were tainted with my stirring feeling of guilt for having people constantly serving me. In the guest house where we spent several nights, my family and I were fed by two young men who were there before we woke to make us fresh, hot aloo paratas. They waited around for us to finish our rum and be ready for dinner, with shy but genuine smiles on their faces. They tried to hold in their laughs when they heard me jokingly belt out Hindi songs from the radio, and although it felt to me like a friendship intruded by a deep language barrier, I was to them a boss.

When traveling through the winding mountain roads, we were only passengers to a personal driver who was at our beckon call for any major or minor excursion we planned. He drove us for hours through Kullu and to Manali and back, waiting for me to pick out a pashmina color that suited my skintone, pulling to the side of the road at discrete turns for restroom breaks, searching for an hour for a location to photograph a sunset, and essentially allowing us to be in charge of our trip while relying on him. When we stopped at restaurants to eat along the way, he refused to sit with us and somehow managed to find wait staff or doormen that he could call friends in every city along the way. The manner in which he scurried off at every opportunity made me feel like he did not want to be seen with us, but in reality it felt unusual for him to have his passengers attempt to include him.

As a stranger to this common etiquette, I felt as though we were not only excluding him individually but also perpetuating a divide between classes that is comfortable to many Indians but painful to watch as a foreigner. After a night of maybe one too many Kingfisher glasses, I broke down explaining this concern to my family.

“He just helps us so willingly, and expects so little in return. He’s left his family for a week to drive us around on vacation and he runs away from any tips force on him. He’s such dedicated worker and that deserves a pairing with a better quality of life,” I pleaded as the knot in my throat tightened. They didn’t sympathize with my view, and pointed out that great service is a staple of their culture, and that ultimately our driver was happy to have pleasant passengers and a steady income. It was the first time in my life I boldly defended “The American Dream” and as delusional I seemed believing it and shedding tears for it, I was somehow emotionally wounded by seeing that an uneducated adult was not able to change careers in his or her lifetime. Much of the American identity, I realized, was about defining an individual identity and being able to do so by a variety of paths. Our driver didn’t necessarily plan on ever getting a different job, but rather put all of his hopes and savings into creating a better life for his daughters. That selflessness was something I had heard about endlessly and sincerely admired, but I had never before felt directly involved in those sacrifices.

I was embarrassed that as open-minded as I pretended to be, I couldn’t wrap my mind around the happiness someone could feel being a server to someone else. By experiencing this internal conflict, my trip to India became more about learning what it was to be an American than what it meant to be half Indian.

This time was going to be different, in my mind. At 19, I felt like I was enough of an adult to approach this trip with both career and personal goals. I traveled to the country for five weeks in hopes of making it less like a vacation and more like a cultural immersion. I dreamt that when I left I would have a grasp on the context of India, enough that I could someday work there as a photojournalist. At the end of the five weeks, I had an innumerable amount of glorified travel images instead of a strong body of work. My personal goal –understanding what part of me was truly and Indian- didn’t go as planned either.

Landing in the hectic and unstoppable motion of Mumbai has always made me feel self-conscious and realistically - very very white. The curious stares from seemingly everyone on the streets created a hyperaware attention to the language I chose, the clothes I wore, and the big expensive camera hanging around my shoulder. This trip in particular – traveling alone and with a purpose – caused an identity crisis I wasn’t prepared to deal with.

The most emotionally difficult experience I had in India was as a tourist with my Aunt Sabrina, my cousin Suhail and his wife Mrunalini. We spent a week in the North, a region of India I had never before seen. The beauty of the place astounded me. It forced me to abandon the images of crowded streets and polluted walkways that I associated with India and begin to absorb the diversity and complexity of the country I was visiting. Snow-capped peaks of hills in the Shiwalik Range of the Himilayas surrounded me and we wandered through small towns that managed to eloquently blend the traditional customs of the people with the undeniable comfort of restaurants and shops that could have accepted credit cards.

My genuine joy and gratitude for the experience were tainted with my stirring feeling of guilt for having people constantly serving me. In the guest house where we spent several nights, my family and I were fed by two young men who were there before we woke to make us fresh, hot aloo paratas. They waited around for us to finish our rum and be ready for dinner, with shy but genuine smiles on their faces. They tried to hold in their laughs when they heard me jokingly belt out Hindi songs from the radio, and although it felt to me like a friendship intruded by a deep language barrier, I was to them a boss.

When traveling through the winding mountain roads, we were only passengers to a personal driver who was at our beckon call for any major or minor excursion we planned. He drove us for hours through Kullu and to Manali and back, waiting for me to pick out a pashmina color that suited my skintone, pulling to the side of the road at discrete turns for restroom breaks, searching for an hour for a location to photograph a sunset, and essentially allowing us to be in charge of our trip while relying on him. When we stopped at restaurants to eat along the way, he refused to sit with us and somehow managed to find wait staff or doormen that he could call friends in every city along the way. The manner in which he scurried off at every opportunity made me feel like he did not want to be seen with us, but in reality it felt unusual for him to have his passengers attempt to include him.

As a stranger to this common etiquette, I felt as though we were not only excluding him individually but also perpetuating a divide between classes that is comfortable to many Indians but painful to watch as a foreigner. After a night of maybe one too many Kingfisher glasses, I broke down explaining this concern to my family.

“He just helps us so willingly, and expects so little in return. He’s left his family for a week to drive us around on vacation and he runs away from any tips force on him. He’s such dedicated worker and that deserves a pairing with a better quality of life,” I pleaded as the knot in my throat tightened. They didn’t sympathize with my view, and pointed out that great service is a staple of their culture, and that ultimately our driver was happy to have pleasant passengers and a steady income. It was the first time in my life I boldly defended “The American Dream” and as delusional I seemed believing it and shedding tears for it, I was somehow emotionally wounded by seeing that an uneducated adult was not able to change careers in his or her lifetime. Much of the American identity, I realized, was about defining an individual identity and being able to do so by a variety of paths. Our driver didn’t necessarily plan on ever getting a different job, but rather put all of his hopes and savings into creating a better life for his daughters. That selflessness was something I had heard about endlessly and sincerely admired, but I had never before felt directly involved in those sacrifices.

I was embarrassed that as open-minded as I pretended to be, I couldn’t wrap my mind around the happiness someone could feel being a server to someone else. By experiencing this internal conflict, my trip to India became more about learning what it was to be an American than what it meant to be half Indian.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)